The Prisoners Paid the Warden's Salary - by a Member of the Post-Dispatch Sunday Magazine Staff

Crane, Missouri

A thick, stocky man with jet black hair stands on the bank of the clear, ice-cold stream that runs between low hills near here and whips the quiet pools with his trout fly, flecks the water again and again, patiently, and then trudges off up the stream. It doesn't seem to matter very much whether he catches any fish. By the look in this fisherman's eyes it is not difficult to tell that fishing is secondary to some tall thinking, pursued along the shady reaches of the stream.

Ben F. Van Dyke came to his camp-farm the other day to rest and recover from what was, he says, the biggest experience in his life. He is unable to speak of certain phases of it without showing the emotional strain he went through. Here on his farm, the old Wiseman (sp?) Mill place, with his wife, he is taking a month to think out what that experience meant and why it ended as it did.

Shortly before William H. (Alfalfa Bill) Murray became Governor of Oklahoma last January he wrote to his old friend, Ben Van Dyke, offering him his choice of eight different State offices. Murray had known Van Dyke since Oklahoma's constitutional convention of 1907. They worked together at that time to formulate Oklahoma's laws. Van Dyke became a successful lawyer at Mangum, Oklahoma. "Alfalfa Bill" followed a somewhat fantastic political career, sure always of at least one thing – the loyalty and support of his friend Van Dyke in Greer County.

One of the offices on the list was that of Warden of the State Penitentiary at McAlester. Van Dyke was not interested in political office, he had never taken an active part in politics – except to aid Murray. His law practice was extensive and demanded most of his time. But he did have a very special interest in becoming warden of a penitentiary. For years, out of his experience in the law, and from his reading of criminology and penology, he had been thinking along the lines of prison reform. He had evolved definite ideas as to how a prison should be run. So strong was his faith in these ideas that he went down to Oklahoma City and told Governor Murray that he would accept the post of Warden.

There followed, as has followed most of Murray's official acts, a mild storm. The Oklahoman and the Oklahoma CIty Times both more or less fixed in their opposition to Murray, severely criticized the appointment. There arose at this time, too, the question of whether Van Dyke's appointment was valid without confirmation by the State Senate, then in session. Murray said it was, and that as long as he was Governor, Van Dyke would be Warden of the penitentiary. Several times he repeated this in print.

Meanwhile, regardless of this tangle, and on advice of the Governor and the Governor's legal adviser, Van Dyke had gone to McAlester to take charge of the penitentiary. He went there, he says now, looking back on the experience, with the terrible fear that perhaps his theories were wrong, that possibly he might make an appalling failure.

But he did not hesitate. He believed, first of all that prisoners should be treated like human beings. His theory is founded on the tenet, which he utters in a solemn voice, "Do unto others as ye would have them do unto you."

"One of the things they said against me was that I was an infidel, an atheist," he says. "But I know, even though I don't belong to any church, who was the Great Teacher of these last 2000 years."

The McAlester prison was begun in 1908. There have been piecemeal additions from time to time ever since. The present capacity is 2100 prisoners. There were 3169 prisoners when Van Dyke took over the office of Warden. Men were sleeping on cots in all the lower corridors.

He found 40 men in solitary confinement – "on high" the phrase is in the Oklahoma penitentiary, because of the fact that the solitary cells are those on the highest tier. They are not, in the strict sense, solitary cells, as they are shared by two men. The windows before these cells were boarded up, so that almost no light and no air reached the inmates.

Van Dyke examined the records of these man. He found, he says, that there had been little or no consistency about commitments to solitary.

One of the 40 men had been put "on high" for leaving half a biscuit uneaten on his plate, three others for attempted escape, and the offenses ranged all the way between these two opposite poles. Van Dyke found, too, that there was apparently no fixed time limit placed upon a stay in solitary. It had been the practice to take each man into the corridor outside the cells for 15 minutes twice a week for an "exercise period."

Of the 40 men three were violently insane. At least a half-dozen gave indication of the onset of tuberculosis. One of Warden Van Dyke's first official acts was to order these men, with the exception of the insane, of course, taken down into the yard for a half-hour in the sun twice a week. The next week he made it three times. And after a fortnight he had each of the men brought into his office.

One of them was a notorious bandit, whose name Van Dyke prefers to withhold. When this man – he can be called Jim Smith – was seated opposite him, the Warden said: "The newspapers make you out to be a pretty bad man. Are you going to help to live that reputation down? I want to take you off solitary and I want you to promise me that you'll behave. I want to do this to save your health and your mind."

Jim Smith hesitated a minute before he said: "Yes, I'll give you my promise."

"But how do I know that you'll keep that promise?"

"I've done a lot of things, Warden, but I've never broken my promise once I've given it."

The other interviews went very much in the same way. Van Dyke says that he experienced almost no difficulty in approaching these men on a human, man to man basis. Many of them told him later that it was the first kindly or even decent word that they had heard from any official source in months, years.

With these men withdrawn from solitary -- and it was only necessary to resort to this punishment once during the time he held office -- Van Dyke started to clean up certain danger spots, fire traps, corridors that had been blocked off with wooden partitions, flimsy construction that had been allowed to stand. But there was an even more pressing problem.

Warden Van Dyke was determined that he would not permit the hired guards to exercise summary disciplinary measures upon the prisoners. After the first two weeks he was confident that he could effect this radical departure in prison methods. He knew, he relates, that already the atmosphere of the prison had somewhat changed. Twenty minutes after the 40 men were taken down from "on high" every prisoner knew about it by the means of the grapevine telegraph, and when Van Dyke next went into the prison yard there were smiles and less of the quiet, intent watchfulness that everyone who is at all familiar with prisons knows as well -- as though a single impulse moved each furtive head to turn and watch the passerby. Van Dyke had brought with him a half-dozen younger men in whom he had complete confidence: Sam Harlan as chief clerk, Curtis Jennings as his private secretary, Howard McLeod as chief sergeant of the guards. And he found a first deputy, Wallace Bond, and a second deputy, Jesse Phillips, who were anxious to co-operate in carrying out the new Warden's ideas. These men set themselves to report all guards who violated Van Dyke's order against summary punishment.

The guards all carried stout clubs, and they had been in the habit, a great many of them, of cracking the head of a convict who violated a prison rule, however unimportant. The custom was, according to Van Dyke, first to curse the offender. And if he tried to explain why he stepped out of line for a moment or why he paused at his machine in the workshop, he got a crack on the head or over the shoulders.

In his first two months as Warden Van Dyke replaced about 50 guards who failed to heed his instructions. Some of them, he explains, were definitely sadists -- with a psychopaths love for inflicting torture and suffering. One man fractured the skull of a prisoner with his club after the prisoner had been shot down in an attempt to escape and it had been necessary to restrain him from beating the man to death with an iron bar.

Another guard, a former Methodist minister, was given to a particularly brutal form of punishment for minor infractions of prison rules and regulations.

He manacled the offending prisoner about the wrists and then suspended him from the side of the cell, often for the entire night. This guard would then keep a close watch on the suspended prisoner and when, because of the intense strain, they attempted to support themselves by digging their toes against the wall, he gave them a good, hard crack with his club.

Frequently, following the dismissal of sadistic guards Van Dyke would be visited by politicians and legislators, who had come to make a protest. The guards had been political appointees. What was the idea of firing them? It was usually sufficient, Van Dyke says, to explain what these men had done. At least an explanation silenced and further outward protest.

Van Dyke's aim was to handle disciplinary problems himself. He posted a notice announcing that any prisoner could write his grievance direct to him, and the guards likewise brought their complaints to the Warden's office.

Sometimes, Van Dyke says, he had as many as a hundred letters from prisoners on his desk in one morning. And it was easy to weed out those which came from professional malcontents and trouble makers. It was easy, too, he says, to see through the shallow pretense of the informers, those men -- part of every prison population -- who seek to advance themselves by reporting violations of the rules and who will even go to the extent of planting evidence against their fellow convicts in order to ingratiate themselves by reporting it.

"Why, I was Superintendent of Schools in towns in Iowa and Kansas for five years before I came to Oklahoma, " Van Dyke says, "and those men weren't essentially different from the boys I had to handle then. They're all human except for the few of low intelligence."

And Van Dyke was busy in other directions. He succeeded in getting through the Legislature a series of appropriations to advance projects for the prison -- $115,000 a year for two years to build new cell blocks that were to serve, under his plan, as a kind of sub-prison for convicts who had demonstrated that they could be trusted. These men, upon release, were to be given special certificates indicating their special trustworthiness, so that they might more quickly win back a place in society. Van Dyke got $25,000 for a new power plant, $20,000 for a cold storage system for the produce raised by the convicts, $10,000 for an extra wall around a new three-acre exercise ground, $10,000 for a tubercular ward.

All this time the controversy continued over whether or not he was rightfully Warden of the prison. But Van Dyke was too busy to pay much attention to it. Then the Governor appointed a business man, Sam Browne, to the post of Warden. But Van Dyke assumed that this was merely a way in which Governor Murray planed to assure him of the post by means of a recess appointment.

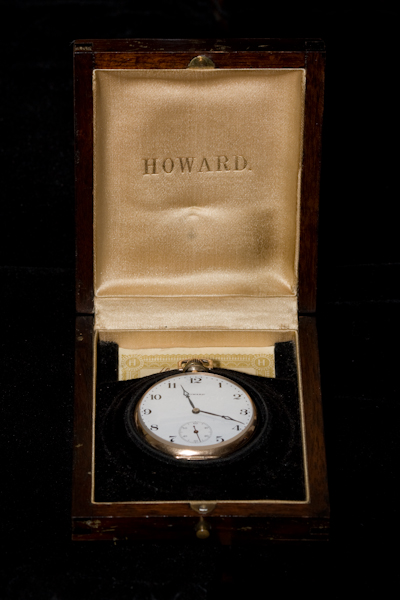

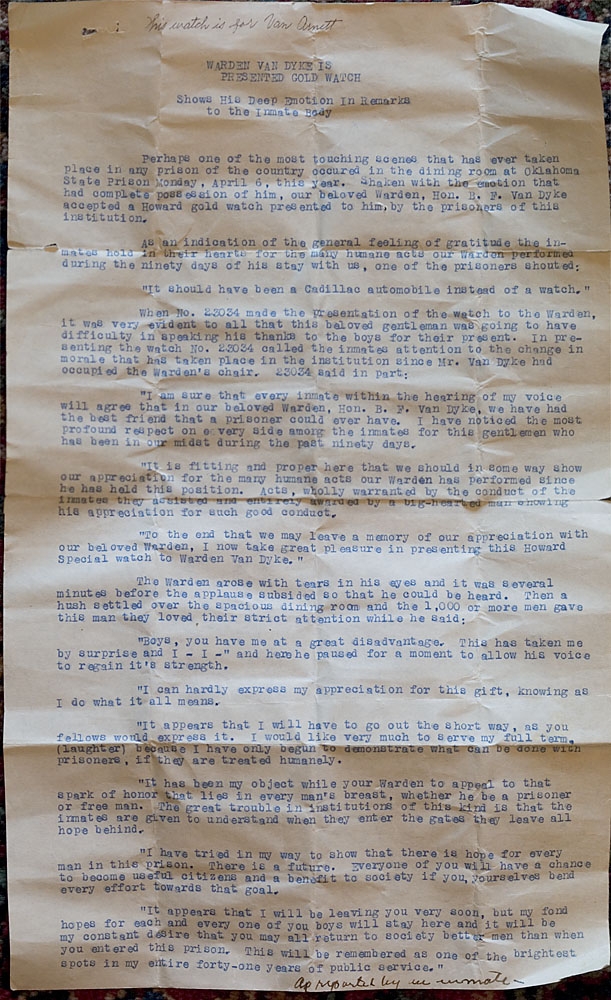

But it appeared shortly afterward that Browne actually was to take charge. Van Dyke was so stunned by this blow that he made no attempt to see Murray. He accepted the dictum. On the day after word of this got around the prison a delegation of prisoners waited on Van Dyke and asked him to come into the dining hall where the first shift of 1039 men had come in to lunch. There, No. 2304, as spokesman, presented him with a gold watch. Van Dyke was so overwhelmed by emotion that for several minutes after the prolonged applause had ceased he could not reply. Even recounting the incident a week later, it was obviously difficult for him to control his emotion.

The prisoners, moreover, had voted to advance him his salary out of their canteen fund of several thousand dollars. They had done this from month to month during the 90 days of Van Dyke's term. And in turn he had assigned to them his claim against the State. But now, when it appeared that he would not be reimbursed at all for his service a majority of the convicts voted to repay the canteen out of their own funds so that Van Dyke would not be $1200 out of pocket.

On the Sunday that he was at the prison for the last time, Van Dyke tried to leave quietly. But a group of convicts -- employees in the office and in the corridors -- gathered to say good-by. Van Dyke says frankly that he broke down at this parting, and so did the men.

"Don't think," he says, "that the conditions in the Oklahoma prison are any exception. I've seen enough penitentiaries to know. Wherever the Warden is not in direct contact with the prisoners and wherever the unrestrained brutality of the guards is permitted, there will be trouble, danger. Those conditions prevail, you can be almost certain, before a riot.

"Convicts are driven to rioting only by extreme abuse and a deep sense of injustice. They are men and they will respond like men if they are treated as such. In my opinion our prisons are the greatest menace society has today. The number released from our prisons exceeds the number of college graduates.

"It seems to me that society makes the prisoner the scapegoat for its bad conscience. For, after all, with our present system of justice, what percentage of those who should be in jail are behind bars?"

We sit on the porch of his camp cabin, looking out over the trout stream. A neighbor drops in and Van Dyke explains his plan for throwing a dam across the stream to better the fishing.

"And besides, I feel in a damning mood," he says, a grim smile about the corners of his mouth.

(click here for a facsimile of the page.)

And here's another report about the watch:

Oddly, there's no mention of any of this in the History of Corrections in Oklahoma website. Perhaps that's because he served for such a short period.

I made a "copy" of this watch as part of the iPhone application Emerald Chronometer (see "McAlester").